×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

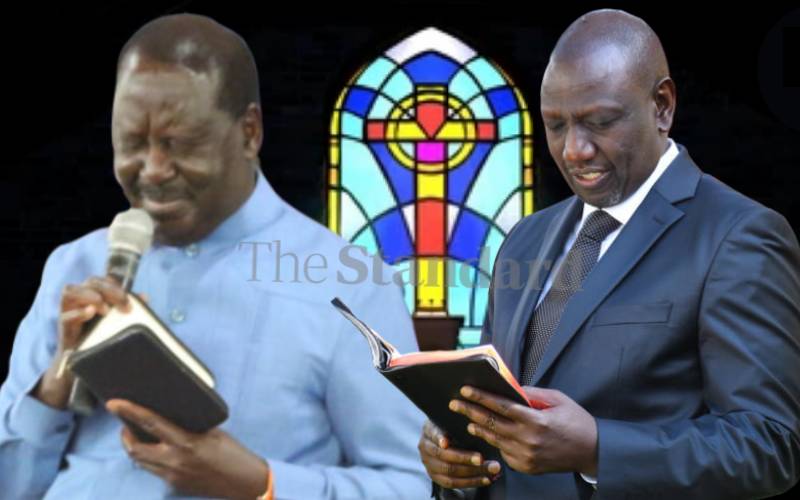

ODM leader Raila Odinga (left) and DP William Ruto. [File, Standard]

In the recent past, the clergy has stepped up efforts to tame “rogue” politicians who have converted church pulpits into campaign platforms.