×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

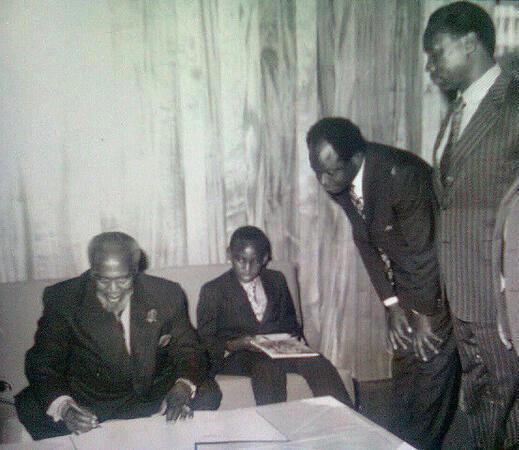

As Kenyans debate who is best placed to lead the country after 2022, this is the right time to take stock of how the institution of the presidency has evolved over the years.

Past presidential epochs in independent Kenya have etched their place in defining the history of the peculiar but versatile people that Kenyans are.