×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

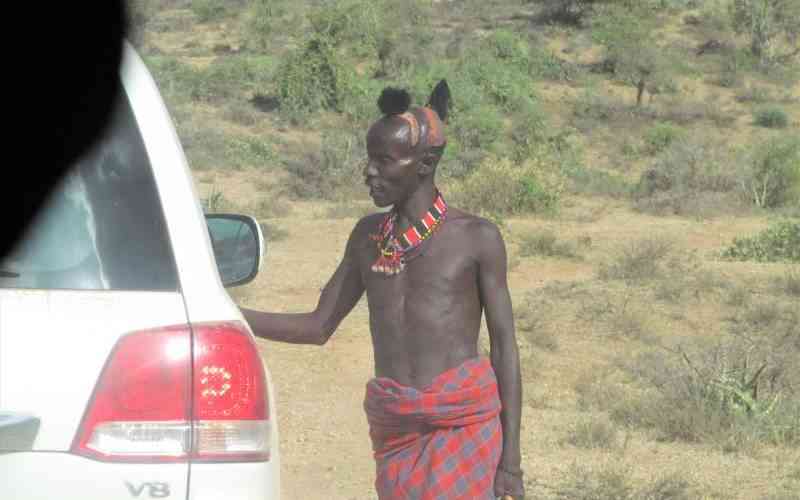

Once shunned and exploited by powerful economic interests, Indigenous peoples worldwide are gaining attention and strength to protect their lands and resources.

This is emerging not only deep in the rainforests of Asia and South America, but also in Kenya and its neighborhood - and is the subject of my recently-published book, Last Days in Naked Valley (Afrologi Media via Amazon).