×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

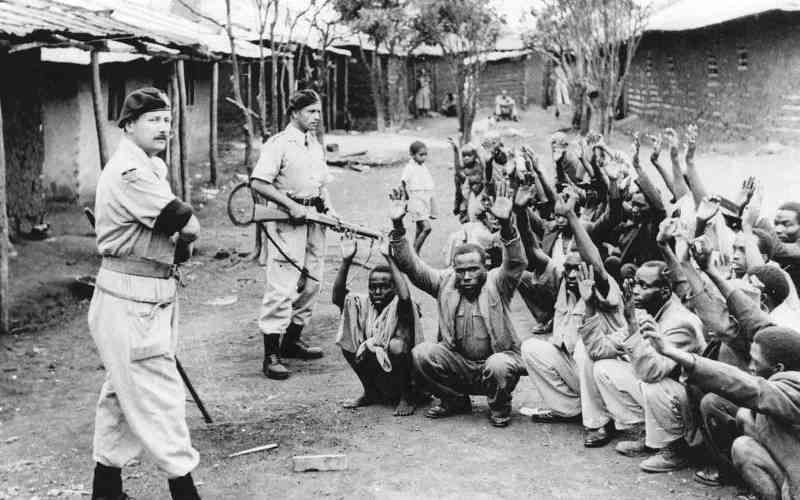

Kenya, and by proxy East Africa has one of the richest historical records in the world. But how many of us know that story? How many of us know where we come from, and how we came to be in our present situation as contemporary Kenyans?

Martin Luther King said that we are not makers of history but made by history. This is apt considering the many challenges we face as Kenyans today.