×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

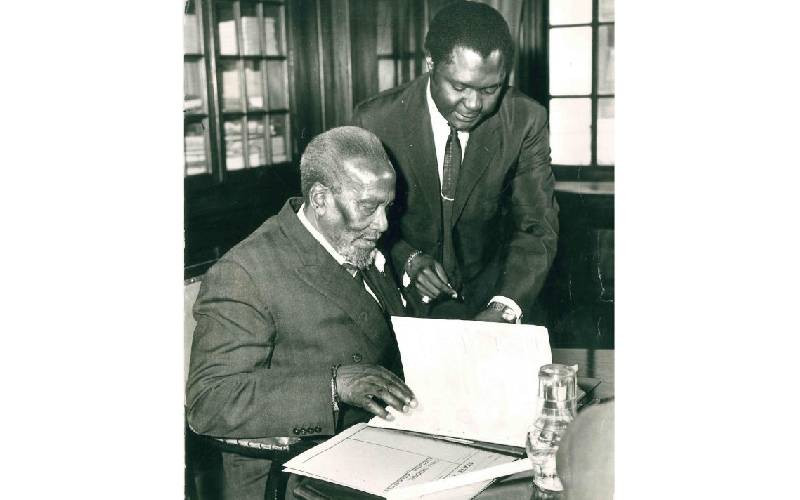

As early as 1960, colonial intelligence reports had marked out Tom Mboya as a future political star and quietly nudged him to claim the void left by the incarceration of Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.

“He has had to contend with colleagues and assistants whose lack of principle, unreliability, dishonesty and narrow outlook make his achievements all the more remarkable,” Director of Intelligence and Security M.C Manby wrote in November of 1960.