×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

The government has revealed a 10-year plan to remove orphaned and vulnerable children from children's homes and orphanages, and transition them to family and community-based care.

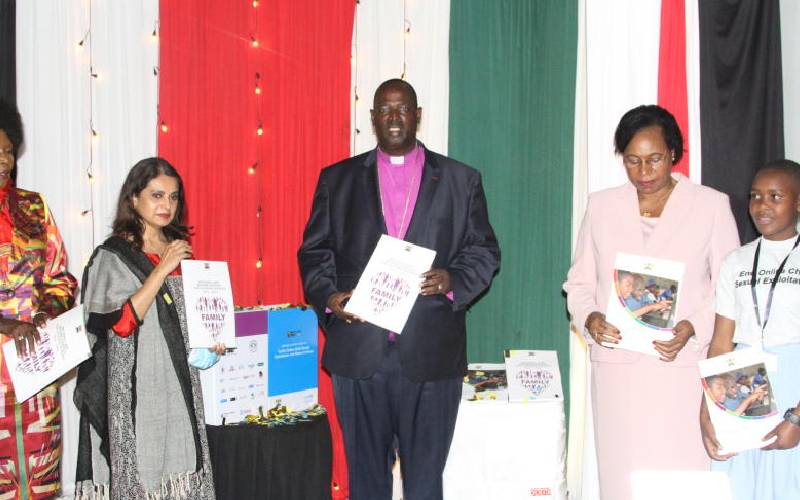

Speaking during the launch of the National Care Reform Strategy for Children in Kenya, Youth and Gender Affairs Cabinet Secretary (CS), Professor Margaret Kobia, said the government will gradually de-institutionalise children in a three-pillar strategy.