×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

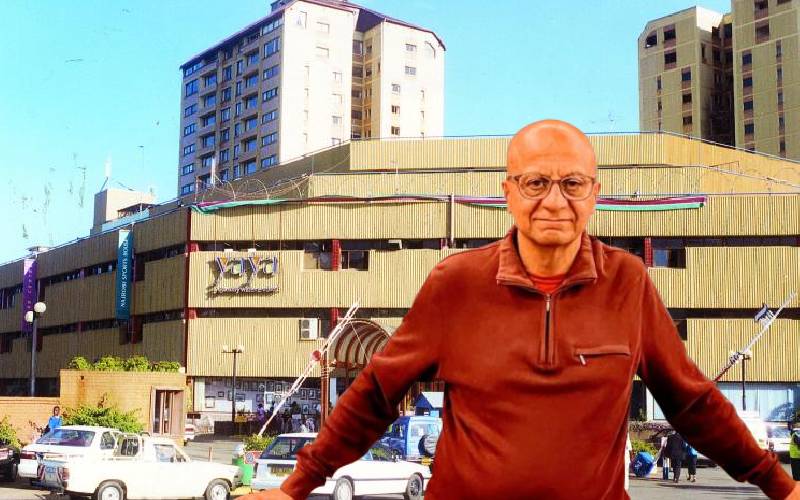

Who owns Yaya Centre? Alnoor Kassam claims that the complex was unfairly taken from Trade Bank depositors. [Courtesy]

Abandoned, desolate and sun-baked for decades, the two towers attached to Yaya Centre blot the otherwise impressive Kilimani skyline.