×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

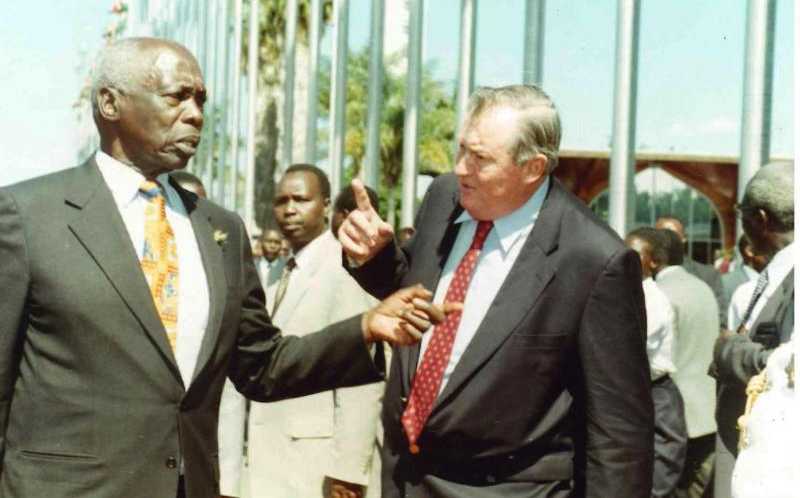

President Daniel arap Moi and Richard: The government could fire and re-hire the strong-willed paleoanthropologist. [Archives, Standard]

For a man who never believed in God, death on a Sunday when most Christians worship their creator could not have been more ironic.