×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

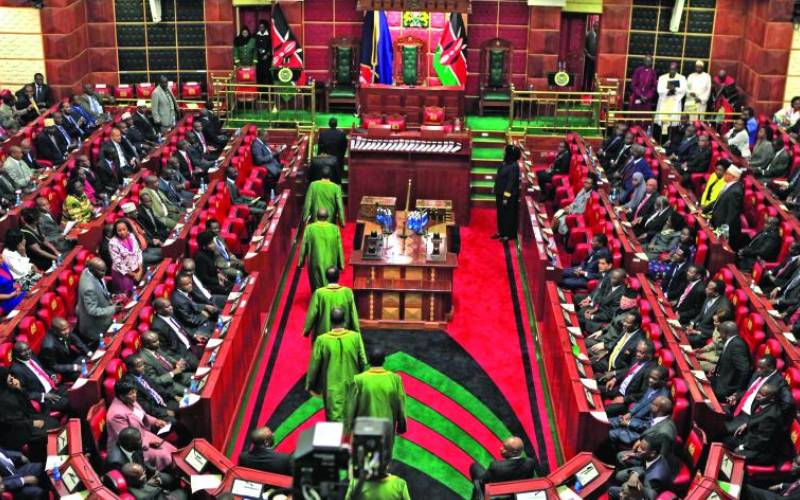

Filibustering has enjoyed relative access owing to the strict timelines to which parliamentarians must adhere. [Courtesy]

Lawmakers worldwide know when they cannot win a debate. While voting by acclamation gives an opening to the louder bunch – sometimes the minority – to win a vote in Parliament, the numbers game in voting by division means that the majority will always win.