×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

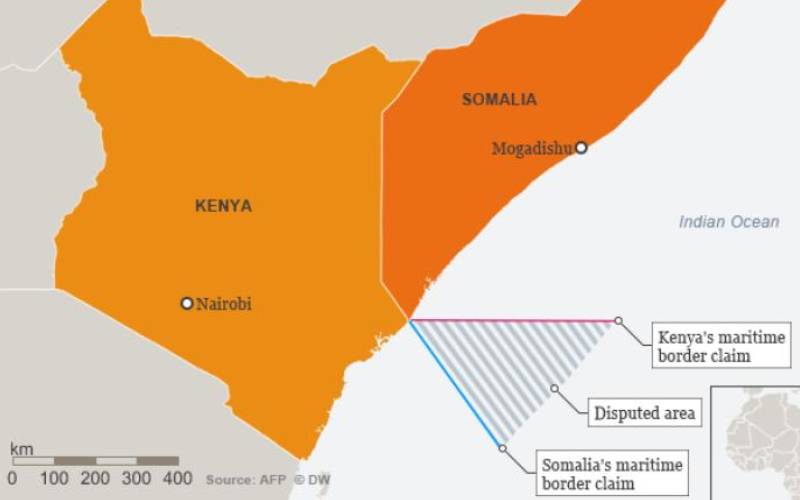

The dispute was filed by Somalia’s Foreign Affairs and Investment Promotion Minister in August 2014. [Courtesy]

Legal experts say the aftermath of today’s judgment on the maritime dispute between Kenya and can only be solved through diplomacy and not the court.