×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

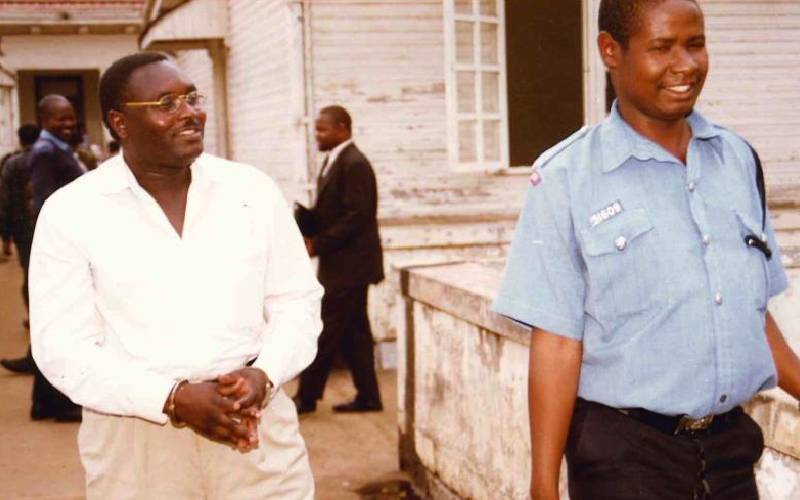

Charles Omondi (left) did several trial runs where he would clear consignments for Citibank. [File, Standard]

When he left his office at Windsor House within Nairobi CBD on the evening of January 4, 1997, Charles Omondi did not imagine that what would follow could be a script for a crime blockbuster movie.