×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

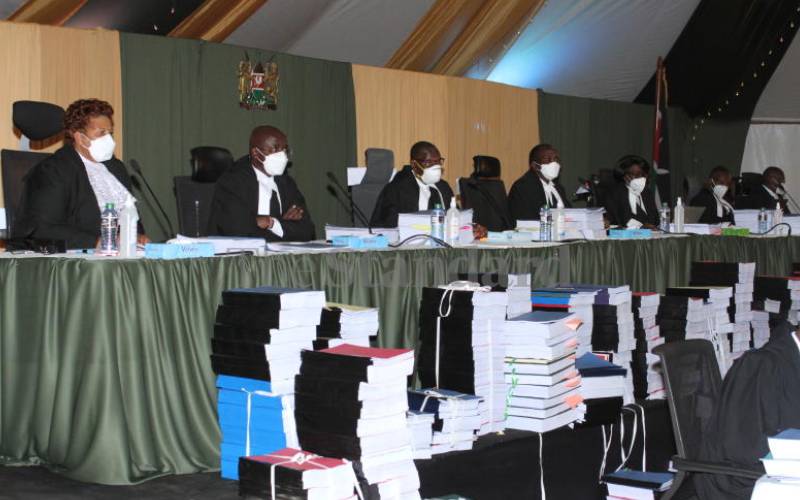

Court of appeal judges Fatuma Sichale, Patrick Kiage, Roselyn Nambuye, Daniel Musinga, Hannah Okwengu, Kairu Gatembe and Francis Tuiyot. July 2, 2021. [Collins Kweyu, Standard]

President Mwai Kibaki promulgated Kenya’s new Constitution 11 years ago, in the presence of the political notables and grandees of the day. Among them was Prime Minister Raila Odinga and Attorney General Amos Wako.