×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

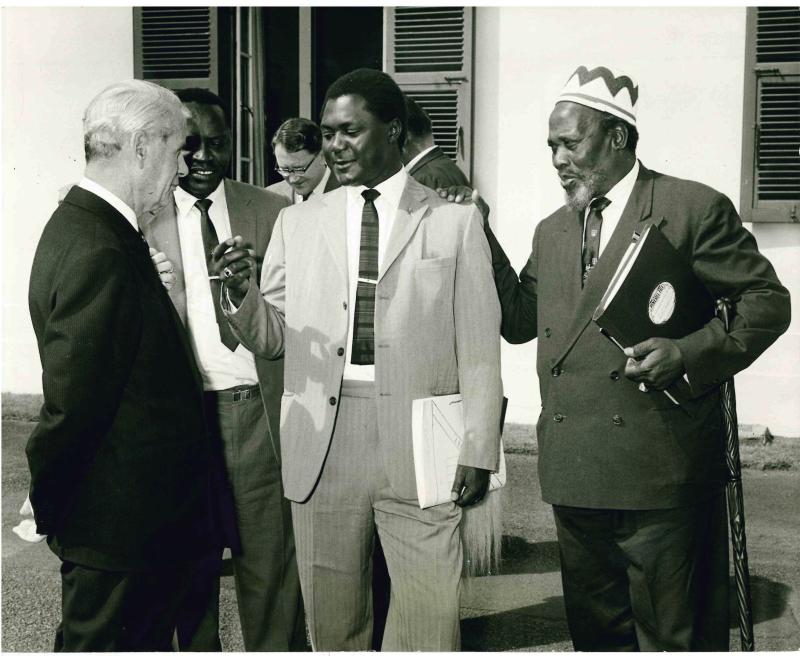

It is 52 years today since Tom Mboya’s life was cut short by an assassin’s bullets on July 5, 1969 a few metres from the statue of a leader many Kenyans living today never got to know.

Still miffed by his lofty achievements in just 39 years of life, pundits wonder how he managed to pull off so much so fast. Mboya was Minister for Economic Planning and Development when he was suddenly stopped in his tracks.