×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

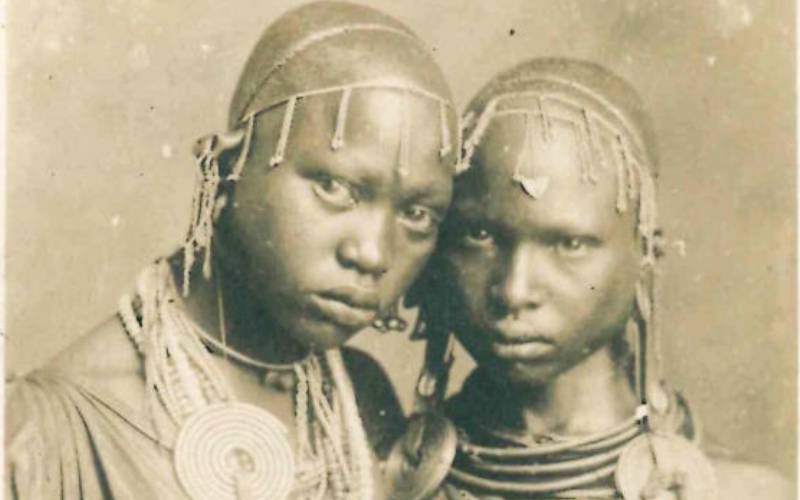

Kamba girls, 1906. [File]

Long before Chief Kivoi Mwendwa made a name for himself and his country, which he introduced as Kinyaa before it was corrupted to Kenya by missionaries around 1849, his kinsmen had established themselves as master jungle trackers and porters.