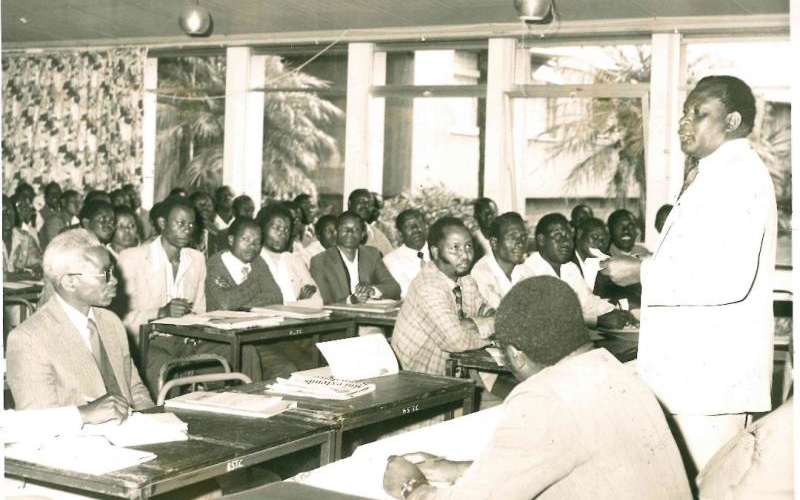

KNUT Sec General Ambrose Adongo addressing headmasters during a workshop on environmental education training at KSTC Nairobi in May 1985.[File,Standard]

Red hot coals beget cold impotent ash. Two weeks to the end of June and an estimated 300,000 teachers are unsure when their next pay hike will be. Their Collective Bargaining Agreement is expiring in a fortnight and the once formidable Kenya National Union of Teachers (Knut) is on its death bed with Secretary General Wilson Sossion under siege; de-registered as a teacher amidst attempts to hound him out of office.