×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

Our lunch is at the Black Gold Café at The Panari Hotel in Nairobi. We nearly changed the venue at the 11th hour. There was so much traffic on Mombasa Road due to the ongoing construction of the Nairobi Expressway. It didn’t help matters that Tanzania’s President Samia Suluhu was also in town.

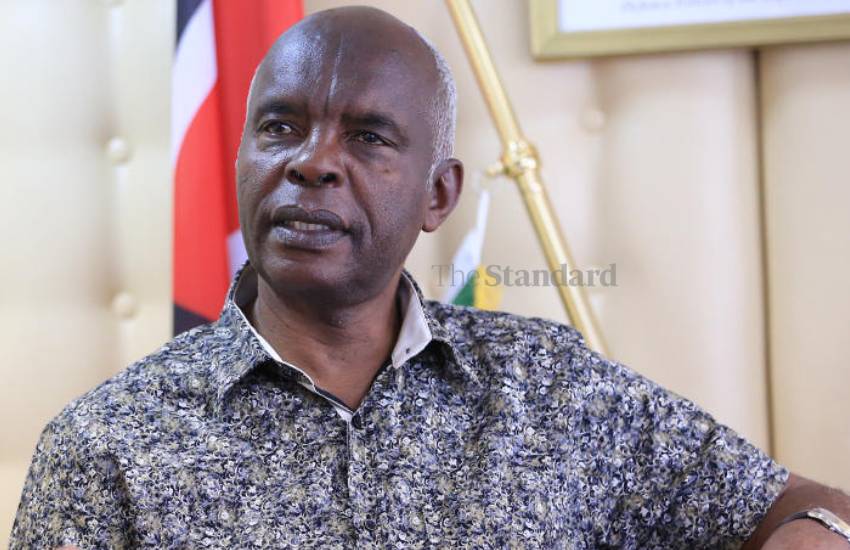

He walked into the restaurant on the ground floor of the building 10 minutes after me and gracefully apologised for keeping me waiting.