×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

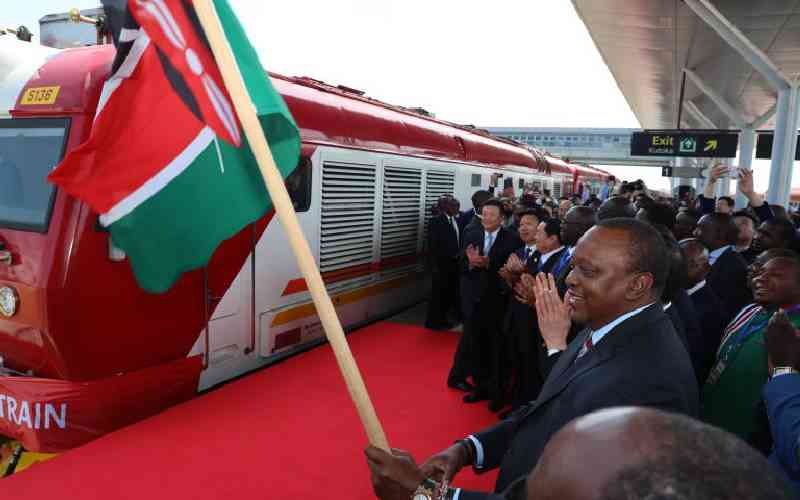

President Uhuru Kenyatta flags off the first freight train, connecting Nairobi to Naivasha's Inland Container Depot, at the Standard Gauge Railway Nairobi Terminus on December 17, 2019. [File, Standard]

The government legally acquired Standard Gauge Railway (SGR), the Supreme Court has ruled.