×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

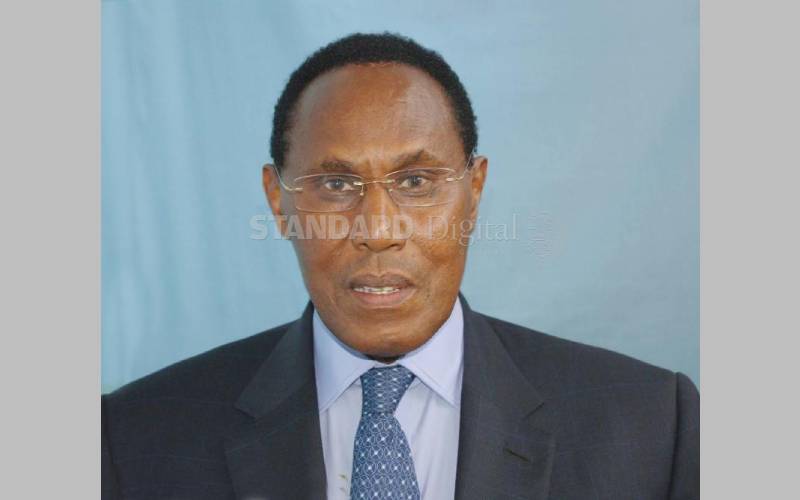

There were two celebrated professors in President Daniel arap Moi’s administration: Moi, the self-proclaimed “Professor of Politics”, and his long-serving Vice President, George Muthengi Saitoti, Professor of Mathematics.