Policy sound-bites, bullet point campaign billboards and boom from the sunroofs of SUVs. However, as John Githongo notes, these elections are yet to produce big galvanising policy ideas for millions of voters.

Traditionally, it has been from among civic organisations and research think-tanks that the best policy manifestos have been crafted. Why is 2022 so different?

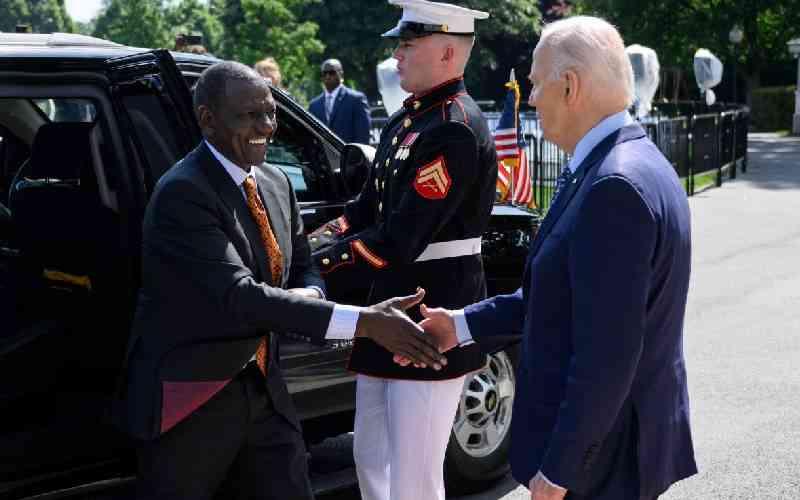

Over the last few weeks, presidential aspirants Raila Odinga and William Ruto spoke to prestigious and influential policy think-tanks like Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and Chatham House on their America and the United Kingdom trips.

This Thursday, Kenya Kwanza leaders Ruto and Musalia Mudavadi shared their economic policies with the Kenya Private Sector Alliance. Raila had met the group earlier. These are important moments for aspirants to test and source ideas from thought-leaders and stakeholders. This must be encouraged.

Despite these interactions, local and national discussions on how to eliminate runaway corruption, gross inequalities, negative ethnicity and expand human rights for all, are yet to happen. While the more cynical of us will argue that these issues do not affect self-interested politicians, I disagree.

Extreme inequalities, lawlessness and marginalisation threaten all future national and county administrations seeking to govern under our Constitution. The impact of less than 8,300 people owning more wealth than 44 million people is plainly visible in our streets, neighbourhoods and in the media.

Too many Kenyans now believe living within our national values and refusing to bribe, or steal will not guarantee their families comfortable and dignified lives. Their pessimism is supported by statistics. Accelerated by corporate tax evasion, corruption and unequal access to jobs, capital, education, and healthcare, the number of millionaires is set to increase by 80 per cent over the next ten years.

One in two Kenyans today do not believe there is equality under the law and twice as many Kenyans fear the police than poverty. We approach these elections with the historic trauma of violent electoral policing coupled with recent spikes of indiscipline, extra-judicial killings and enforced disappearances linked to police officers.

Citizens are themselves increasingly less civil, more toxic, and prone to public violence as we saw in that recent savage sexual assault involving boda boda riders.

A few months ago, the state was forced to militarily intervene in protracted conflicts in Laikipia and Samburu counties. Now it is the turn of Baringo, Turkana and West Pokot to demand action. None of the political parties have articulated clear strategies to transform the sharp tensions between pastoralist communities over land ownership and land use or reform policing and the security sector.

Civic organisations have deep policy and programmatic expertise in all these areas. Despite domestic policy neglect and dwindling foreign funding, the release of the 2021/2022 Annual NGO Sector report on Monday reveals the resourcefulness of the NGO sector for those wishing to govern.

Last year, 2,712 NGOs invested Sh158.7 billion and employed 42,308 Kenyan staff, 37,756 interns and volunteers and 5,040 expatriate employees in Kenya and East Africa. Some Sh25 billion was spent assisting the state to deliver on infrastructure expansion and the right to health, food, and jobs.

Over Covid-19, NGOs scaled up building community capacities for empowerment, self-reliance, and joint advocacy by 2,645 per cent according to the NGO Coordination Bureau. Twenty associations representing 85,000 health-workers held their very first convention on Wednesday. They, like the 23,000 strong accountants of ICPAK, 11,100 affiliated Amalgamated Union of Kenya Metal Workers, 17,000 Law Society of Kenya members and tens of community leaders from the Social Justice Centres Working Group know from experience how to transform their sectors and what they can offer incoming administrations. Despite this, future governors, MCAs, MPs, and presidential aspirants have yet to substantively engage them.

Ignoring the deeper foundations of our disenchanted, divided, and disputatious nation comes at a cost for us all. The centre may just snap in the next five years if it is not addressed. NGOs and civic associations could hold the key to avoiding this. Anyone listening?

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.