On August 23, 1973 an escaped convict entered into a bank in Sweden. Jan-Erik Olsson fired at the ceiling with his loaded submachine gun and shouted, “The party has just begun!”

After wounding a policeman who had responded to a silent alarm, the robber took four bank employees hostage. Three of the four hostages were female. Jan-Erik Olsson demanded money, a getaway car and for the release of an imprisoned convict. He also demanded to be allowed to leave with the four hostages to ensure his safe passage.

Holed up inside the bank’s vault, the hostages forged an unexpected bond with Olsson. He draped a wool jacket over the shoulders of one hostage when she began to shiver, soothed her when she had a bad dream and gave her a bullet from his gun as a keepsake. Olsson consoled another hostage when she couldn’t reach her family by phone and asked her not to give up trying to reach them. When the third hostage complained of claustrophobia Olsson allowed her to walk outside the vault attached to a 30-foot rope. The fourth hostage was a man and when he was interviewed later he said that Olson treated all hostages very well.

Relaxed and jovial

By the second day, the hostages were on a first-name basis with Olsson and they started to fear the police more than him. The hostages were relaxed and jovial with Olsson but hostile to the police. The hostages feared that they would also lose their lives if the police attacked Olsson.

Five days later, on the night of August 28, the hostages were rescued. The police pumped teargas into the bank’s vault and Olsson surrendered. The reaction of the hostages to the rescue was not as expected. The police called for the hostages to come out first, but the four hostages refused. The hostages believed the police would shoot Olsson if they left him behind and they wanted to protect him. In the doorway of the vault, Olsson and the hostages embraced, kissed and shook hands.

The hostages’ seemingly irrational attachment to Olsson puzzled the police and the public. The police even investigated one of the female hostages suspecting that she was part of the robbery: she was not. Psychiatrists explained that the hostages became emotionally indebted to Olsson, and not the police, for being spared death. Within months of the siege, a criminologist dubbed the strange phenomenon the “Stockholm Syndrome.”

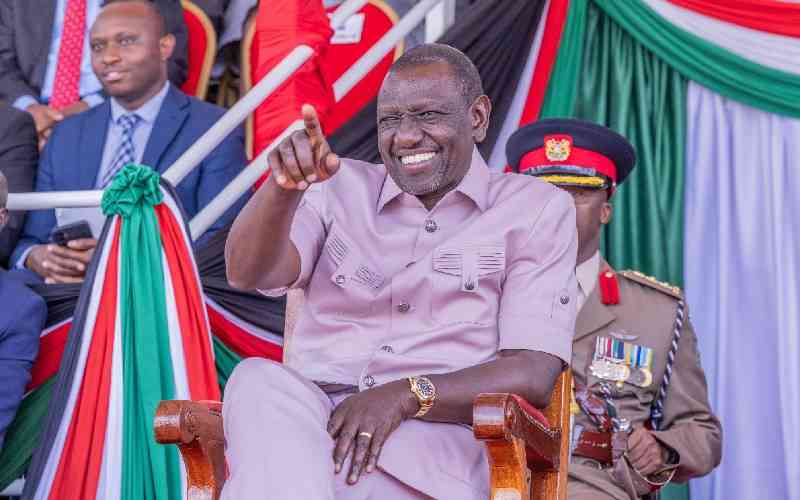

Two days before the swearing in of the President, a friend remarked that: “It has never mattered to me who is at the helm. The end effect is the same in my opinion. There is stupidity in citizens’ belief that politicians will sort out their problems.” This was followed by a rather robust debate on whether or not it is naive to expect leadership from those we elect to be our leaders.

Am I naive to expect more from our country’s leadership? From those elected and also those in the opposition and one day waiting for or hoping to be elected?

For many years I have heard of the “Stockholm Syndrome”, but I had never known of the story behind the phenomenon. It is only after the strange “leaders who are not leaders” debate that I decided to look into the story behind it and to share it.

I believe that if ever there was a country that was a classic example of citizens suffering the Stockholm syndrome it would be Kenya. We have become pawns in the Games of Kenya’s Throne and as we are felled we cheer and with frenzy defend leaders who have taken the country hostage to rob and plunder.

The writer is an advocate of the High Court of Kenya. [email protected]

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.