×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

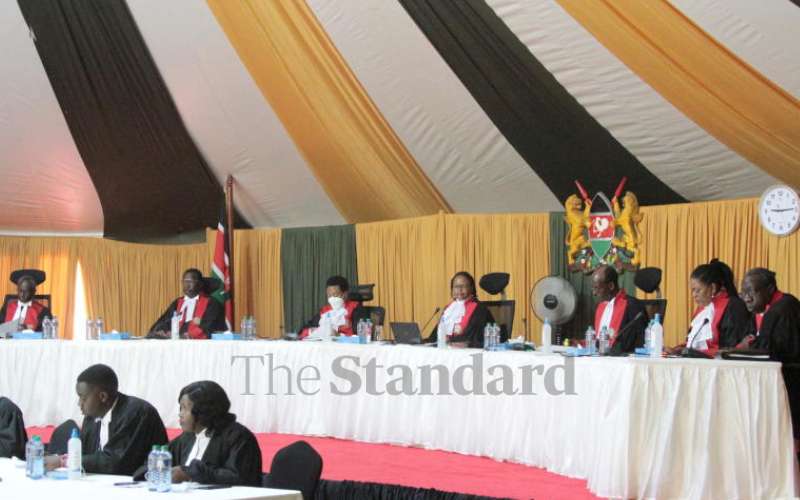

The BBI judgment did its best to prove wrong those people who portend to predict judicial outcomes. [File, Standard]

The Supreme Court of Kenya rendered its awaited verdict on the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) last Thursday.