×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

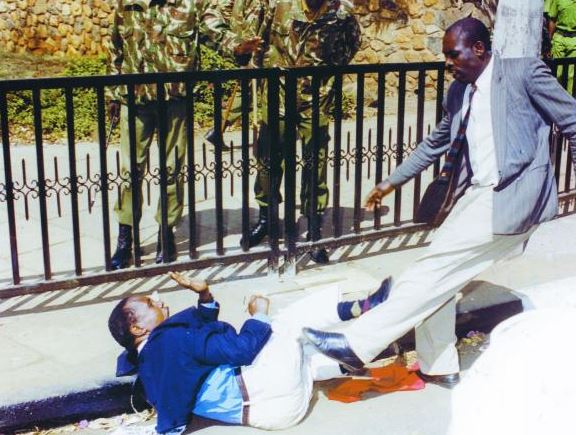

The image of retired Reverend Timothy Njoya lying helpless on the ground (pictured), hands stretched to shield himself from the batons as goons rained blows remains immortalised in the history of the country.