By MOSES MICHIRA

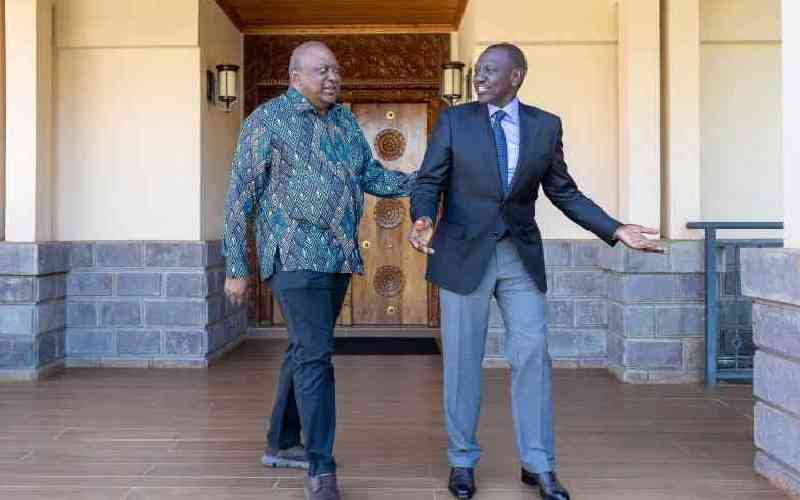

As President Uhuru Kenyatta called for the integration of the African Continent in his address at the just concluded World Economic Forum held in Cape Town, he was touching on a union that Kenya and her East African neighbours have grappled with for over 50 years.

President Kenyatta said the prosperity of the continent lay in the economic integration of the 54 countries to mirror the European Union, and cited the current fragmentation of Africa as largely responsible for soaring poverty.

African countries were competing amongst themselves rather than working together to enhance trade and investment, according to Mr Kenyatta, which compounded a problem that was the basis for the formation of the East Africa Community.

Closer cooperation would boost commerce among the individual countries, just as it was anticipated under the proposed East Africa Federation in the 1960s to bring together Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika with Nairobi as its capital.

It was envisaged that the federation, currently operating as the East Africa Community, would become a political union with a common currency to be used across the member countries.

Federal capital

Today, the membership of the East African Community has been expanded to include Rwanda and Burundi, but the relations between the five countries are still far from a political federation, while the intended integration remains little more than the subject of boardroom discussions.

Yet East African regional politics were at the centre of the contest between Kenya’s independence parties, Kanu and Kadu, back in 1963, with leaders in the former claiming that the constitution they had presented would enable Nairobi to become the federal capital.

On this day in 1963, Asian and European Kanu delegates meeting in Nairobi said that their party’s constitution would help deal with problems the city was facing like unemployment while boosting investment in housing.

At the time, just months ahead of independence and self-governance, Africanisation was seen as a big issue, with the immigrant, community which supported the idea of a regional federation, fearful of possible alienation and even, racial discrimination.

Kanu’s chief executive Mwai Kibaki said the party would ensure internal integration between the native community and the immigrants, especially within Nairobi where social services like health facilities and schools that were for different groupings.

“We must have ways of integrating the schools, parties and the civil service,” said Mr Kibaki, who was later to become Kenya’s President and a strong campaigner for the regional integration in the EAC.

It would be tragic if Kenya produced a situation as in the southern United States in reverse, the Standard quoted Mr Kibaki as saying.

Mr P D Marrian told the party’s meeting that Nairobi was a natural choice as the federal capital, which had been endorsed by both Tanganyika and Uganda, and that both countries were in support of Kanu as the country’s nationalist party.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Nairobi, Mr Marrian claimed, lay at a central location in comparison with any other potential candidates for the capital, plus it had been picked to host several agencies of the United Nations and top global banks.

In fact, the EAC members agreed to have the regional offices in Arusha, Tanzania upon its formal establishment in 1967, but Nairobi is still regarded as the regional financial capital where global firms have established their headquarters.

Strained relations among the three founder member countries led to the dissolution of the EAC in 1977, reversing the gains made towards the proposed integration and introducing a fresh challenge to cross-border trade.

The main reasons given for the collapse of the EAC were the lack of political will and the disproportionate sharing of benefits of the community among the partner states, owing to the differences in their levels of development.

Kenya, it was feared, was getting the biggest share of the revenues accruing from the economic bloc because it had a good transport network, energy and industries, thereby attracting most investments.

It was not until 2000 that the EAC was revived after years of negotiations between the leaders of the three original member countries, even though the mutual benefits of integration were obvious.

The progress is still slow, however. The arrest and deportation of a Kenyan at the Entebbe International Airport by Ugandan authorities two years ago was typical in confirming fears that the regional integration and the free flow of people across borders was yet to be achieved.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.