×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

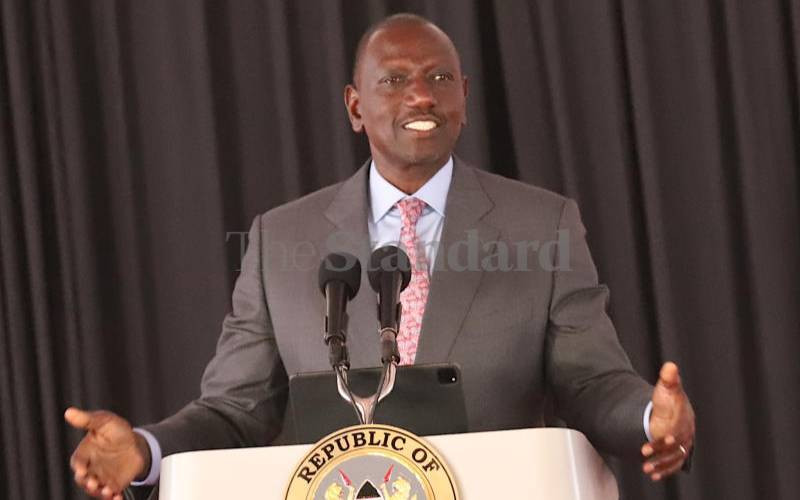

What kind of legacy is President William Ruto likely to leave behind? This is an important question to ask as he starts his first full fiscal year.

I hope President Ruto constantly thinks about his legacy and will not wait to scramble at the end like his immediate predecessor did.