×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

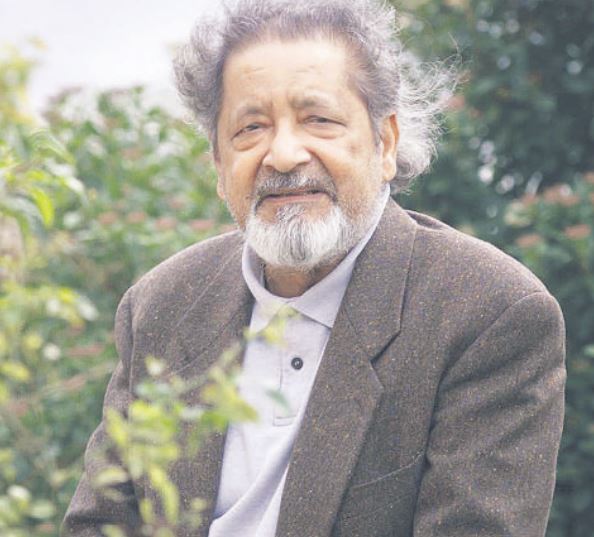

The death of renowned author VS Naipaul last Saturday, August 11, in London, sent the literary world into mourning and, as it happens, sparked an examination into his legacy.

One of the best writers to have come from the Caribbean, Naipaul won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2001 for “having united perceptive narrative and incorruptible scrutiny in works that compel us to see the presence of suppressed histories”.