Kenya’s healthcare market has evolved significantly over the past decades, driven by demographic shifts, technological advances and major policy reforms.

Yet, the overlap between public and private healthcare services, which has contributed to a complex and often inefficient system remains one of the most pressing challenges.

Addressing these challenges requires a united effort from the government, private sector, and development partners to bring a lasting change.

The Kenya Healthcare Federation (KHF), representing the private health sector, reports that public and private hospitals serve roughly half of Kenya’s population each.

Keep Reading

- Private sector contributing 50pc to Kenya's healthcare system, report

- State to refund patients who paid out-of-pocket after SHA rollout

- Private hospitals suspend services under SHA countrywide

- Transition to SHA still facing turbulence- top Health official

Private institutions fill critical gaps left by public hospitals, which often face capacity and resource constraints. Despite their vital role, the blurred lines between public and private healthcare lead to ethical concerns and inefficiencies, with some doctors working in both sectors simultaneously.

This issue becomes even more glaring when doctors and public hospital staff own or operate private pharmacies, clinics and labs. This dual role often raises ethical red flags as public resources may be misused to benefit private interests. Such practices negatively impact the quality of public healthcare, with patients being exploited and overcharged for services that should be subsidized or offered freely.

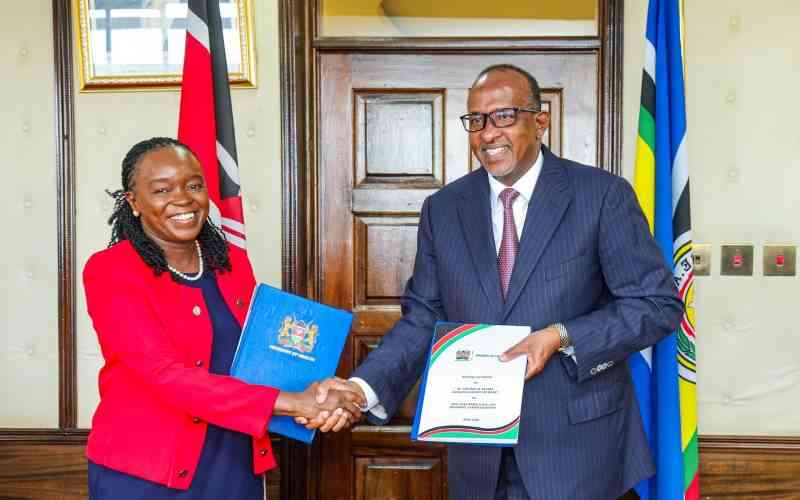

The Ministry of Health, in partnership with USAID and Population Services Kenya (PS Kenya), recently released a report titled, ‘The State of Kenya’s Health Market 2024’, which emphasises the need for reforms to address the conflicts of interest in both public and private hospitals and the deep-rooted issues in the healthcare sector.

The report, based on assessments across six counties - including Nairobi, Mombasa, Kisumu, Nakuru, Uasin Gishu and Homa Bay - highlights how private facilities help fill gaps, particularly in urban areas where demand is high.

A crucial factor in shaping and improving Kenya’s healthcare system is the availability of quality data. Data enables both the public and private sectors to monitor, analyse and shape national markets, providing insight into consumer needs and behaviour. The report highlights that the overall score for market data is 40 per cent, indicating significant gaps in this area.

Dr Martin Sirengo, the Directorate of Health Sector Coordination, Intergovernmental Relations and International Health Relations highlights the need for public-private partnerships in addressing this challenge during the dissemination event.

“This research is essential for both national and county governments, and it highlights the importance of public-private partnerships in reshaping our healthcare system,” he says.

The issue of doctors referring patients from public hospitals to private facilities for services that should be available within the public system has been well-documented.

According to a USAID report, “Patients are frequently directed to private facilities for services that should be available in the public system.” This disproportionately affects low-income patients, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation.

These issues erode public trust in the healthcare system, creating a two-tiered system where wealthier patients receive superior care in private facilities, while lower-income populations are left to depend on increasingly underfunded public hospitals.

A critical factor in improving Kenya’s healthcare system is the availability of quality data to monitor, analyse and shape both public and private markets.

Effective data systems provide insight into consumer needs, allowing healthcare providers to address gaps in care and improve service delivery. However, the 2022 World Health Organization (WHO) report on global health system strengthening emphasises that Kenya’s healthcare data systems, while improving, remain underdeveloped in several areas.

Kenya has implemented multiple data systems, including the Kenya Health Information System (KHIS), Kenya Health Research Observatory (KHRO), and Logistics Management Information System (LMIS). However, these systems are not fully integrated. Much of the data remains isolated, especially in the private sector, limiting policy makers’ ability to make informed decisions.

Dr Lyndon Marani, a Technical Advisor for the USAID PSE Program, further emphasises this challenge.

“Kenya’s health market is vast, covering a wide range of services and products. These counties were selected to help identify key opportunities for improving market efficiency and patient outcomes,” he says.

He adds that there is need for a solid structure in managing healthcare across all counties, a sentiment echoed by many other healthcare leaders.

“The Kenya partnership and coordination framework offers a mechanism for managing the entire healthcare market,” Dr Marani stresses, highlighting the need for better coordination across public and private stakeholders.

The report assigns an overall score of 60 per cent for market institutions, recognising that while Kenya has made some progress, significant improvements are still needed. Key market functions, such as financing, procurement, supply chain management and regulation, require greater coordination to ensure that they support equitable access to healthcare.

Capacity for conducting market analysis and forecasting also remains low. Kenya’s overall score for market analysis, according to the report and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), is 40 per cent.

This reveals a significant need for technical tools to better understand market barriers and to forecast demand. Without this, it becomes difficult to plan effectively and ensure equitable access to care.

Leadership within both the public and private healthcare sectors in Kenya is another area where improvement is needed. The Kenya Healthcare Partnership and Coordination Framework, established in 2018, was intended to provide guidance for national and county-level coordination. However, implementation has been slow, particularly at the county level, where coordination frameworks often vary widely.

Dr Sirengo addresses the need for more robust leadership and partnerships, saying, “The time has come for the public and private sector to establish strategic partnerships and deliver UHC in a sustainable manner. This partnership is essential for addressing gaps in leadership and coordination between the two sectors.”

On the shortfall, Margaret Njenga, the CEO, PS Kenya, says, “As much as we have made progress as a country, we are yet to reach the recommended Abuja Declaration of 15 per cent health financing. Right now, we are at 11 per cent, and much more needs to be done.”

“We are bringing in the government, development partners, and the private sector so that patients can get high-quality services that are affordable,” Njenga adds. This collaborative approach is essential for sustainable progress in the sector.

This shortfall leaves many counties dependent on donor funding, especially in key areas such as maternal health and HIV/AIDS care. Over-reliance on donor funds exposes Kenya’s healthcare system to risks, particularly when funding is reduced or redirected, leaving critical programmes underfunded.

The report also highlights the risk posed by Kenya’s over-reliance on donor funding. Many counties rely almost entirely on donor support for key health programs, including maternal healthcare. This dependency exposes the healthcare system to vulnerabilities, particularly when donor funding is reduced or redirected.

“With all these interventions, why has the maternal mortality ratio not come down? We need to find answers to this problem,” said Dr Sirengo. His observation underscores the persistent challenges that Kenya faces, despite the influx of donor support and targeted programs aimed at maternal health.

Kenya’s healthcare supply chain presents a mixed picture. While there is infrastructure in place, particularly in urban areas, local manufacturing remains underutilised.

Sylvia Wamuhu, the USAID PSE Program Chief of Party, calls for a greater focus on building domestic capacity. “Buy Kenya, Build Kenya.”

Despite these initiatives, many locally produced health products are often viewed as substandard.

The supply chain also faces challenges related to cash flow, procurement delays, and inefficiencies in rural areas, where chronic shortages of essential medicines persist. The World Health Organization’s guidelines on health system resilience suggest that improved local manufacturing and supply chain coordination would significantly enhance Kenya’s ability to meet demand, particularly in remote regions.

Pricing is another critical barrier to healthcare access in Kenya. The private sector, particularly hospitals and pharmacies, often has significant discretion over costing, resulting in disparities across regions. The report assigns a 40 per cent score to Kenya’s pricing mechanisms, noting the absence of clear price control policies.

The Global Fund has emphasised the importance of equitable pricing policies, particularly in low- and middle-income countries like Kenya. By implementing price controls, Kenya could reduce healthcare costs and make essential services more affordable for the majority of its population.

Private sector players, particularly hospitals and pharmacies, have significant discretion over pricing, leading to disparities in access to care. While initiatives like the shift to the Social Health Authority (SHA) and the promotion of local manufacturing aim to reduce costs, without explicit price controls, healthcare remains unaffordable for many.

Quality control is essential for Kenya’s growing healthcare system, particularly as local manufacturing ramps up. WHO standards for healthcare products and services must be strictly enforced to ensure that locally produced goods meet international standards. A commitment to quality to overcome the stigma that local products are inferior is needful.

Kenya’s healthcare market is diverse and vibrant, but challenges such as financing, supply chain inefficiencies and a lack of data integration hinder progress. By addressing these issues, Kenya can move closer to its goal of achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

The path forward lies in stronger public-private partnerships, increased investment in local manufacturing and improved market governance.

With sustained efforts from the government, private sector, and development partners, Kenya’s healthcare system can be transformed to serve all its citizens more equitably.