×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

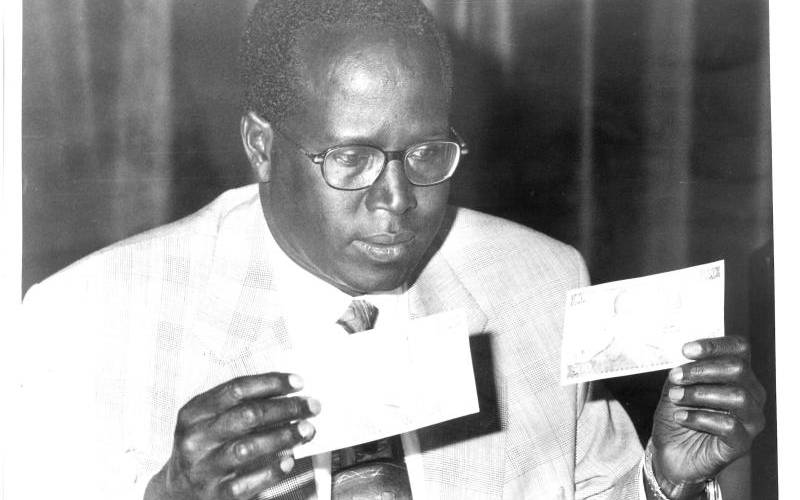

Micah Cheresem, then CBK Governor as he displayed the new Sh500 notes in 1998.

When then 42-year-old Micah Cheserem took over from Eric Kotut as the Governor of scandal-hit Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) in 1993, there were murmurs.