×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

If you were to visit Rwathia in search of the secret to becoming a billionaire, you would be disappointed.

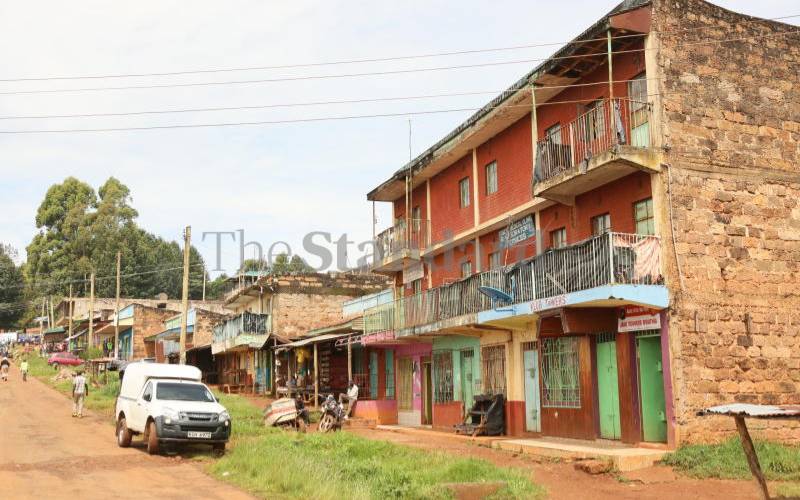

The region that spawned titans of industry is a cookie-cutter model of rural Kenya. The trading centre is perhaps the most underwhelming – a single road with two rows of buildings that have shops facing the street and living quarters in the back.