×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

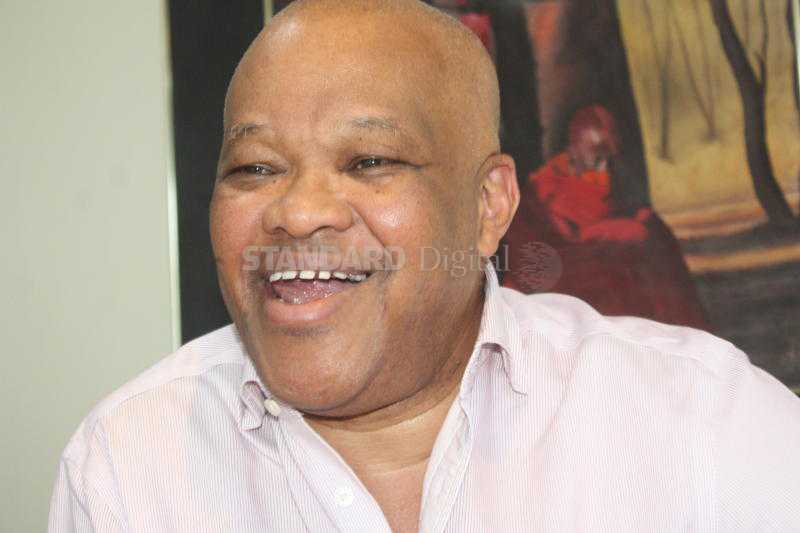

When he talks, he does so with a stutter, but anyone who has faced him at the negotiating table will tell you this does not get in the way of making that crucial point that clinches the deal.

John Ngumi, a seasoned investment banker who has had a hand in a web of mega financial deals spanning the continent and beyond, is astute and inventive in business decisions.