×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

|

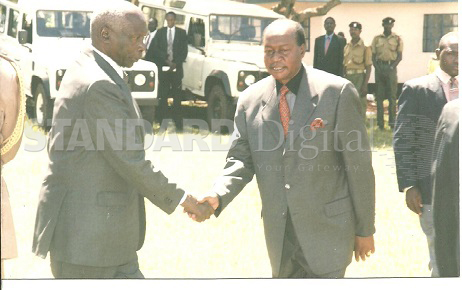

| Retired President Daniel Moi and Phares Kanindo. [PHOTO: FILE] |

One of the most striking features of the Kenyan sugar belt is the sad song of the guinea fowl. In Song of Lawino, the late Okot p’Bitek says that this mournful sound is the spotted bird’s way of asking God why, of all the animals under the sun, only it was slapped with a bald head.

‘Awendo’ is the name given by the Luo to the guinea fowl, and from which a sleepy town in South Nyanza derives its name. The fowl’s sighs are potent echoes of these regions’ sickening loneliness before independence.