×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

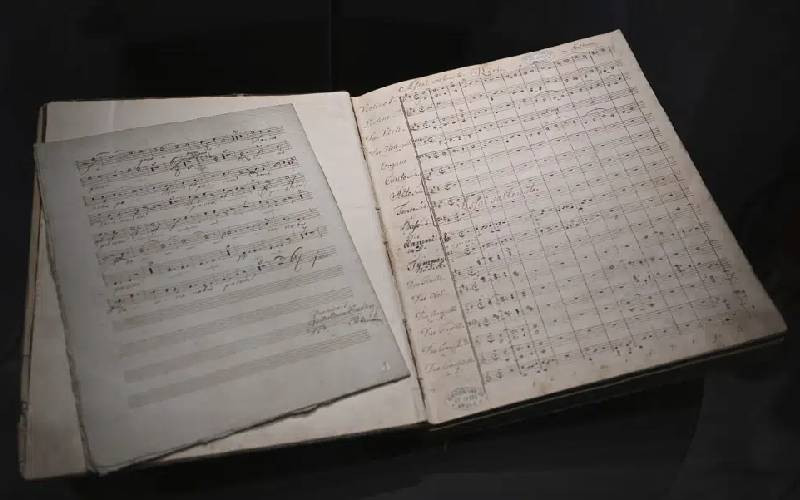

A Ludwig van Beethoven's music manuscript, is seen in the Moravian Museum's collection in Brno on Nov. 30 2022, in Brno, Slovakia. [AP Photo]

A musical manuscript handwritten by Ludwig van Beethoven is getting returned to the heirs of the richest family in pre-World War II Czechoslovakia, whose members had to flee the country to escape the Holocaust.