The dispute over the sharing of 42,000 acres of land in Mwea settlement scheme in Embu County is threatening to turn the area in a battleground, sucking in Embu, Mbeere, Kikuyu and Kamba ethnic communities into a fatal conflict that could result in many deaths and delay the economic utilization of the vast land.

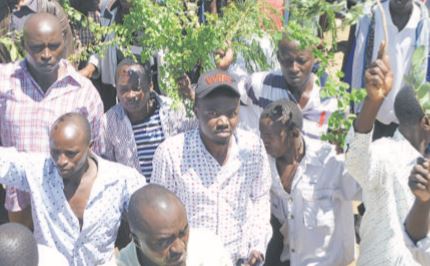

A recent visit to the area by Wiper Leader Kalonzo Musyoka was meant to give moral support to the Kamba claimants of that which is under Embu County. Within the county itself, dispute by perennial rivals Embu and Mbeere tribes represent another fault line, as do claims by the Kirinyaga people that the land was stolen from them when the two were a single administrative unit.