×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

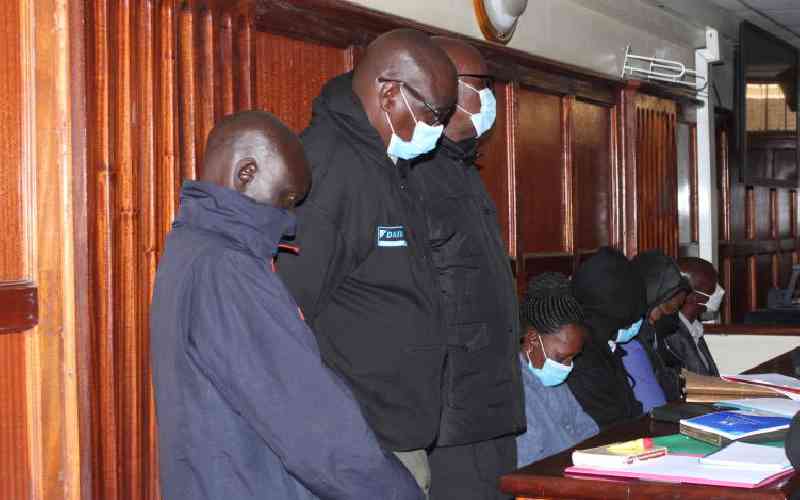

In July 2024, a landmark ruling by High Court Judge Kanyi Kimondo ordered 11 Senior Police Officers to take a plea over the death of six-month-old Baby Samantha Pendo, who lost her life during police operations in Kisumu following the contested 2017 General Elections.

This ruling represents the first time that the ICA has been applied in Kenya, setting a potential precedent for future cases involving serious human rights violations.