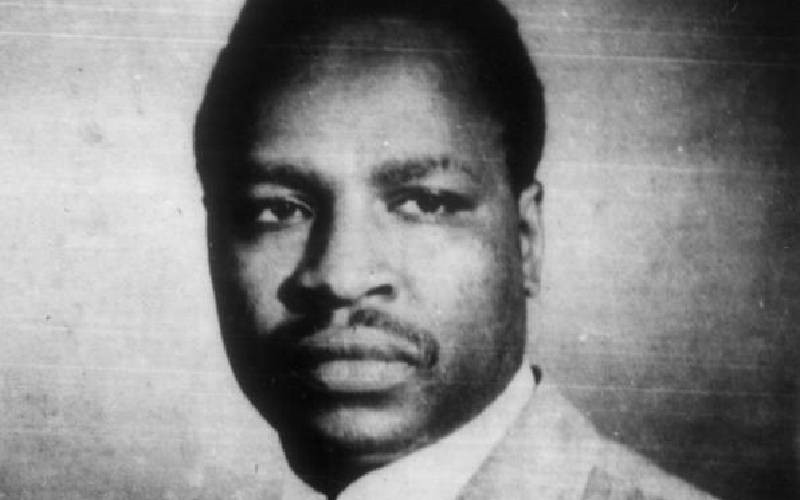

On 2 March 1975, JM, as Josiah Mwangi Kariuki was popularly known, was assassinated. In the 10 years from 1964, all the individuals who the Kenyatta regime or its expectant successor(s), believed, could be centres of an alternative leadership to them came to be assassinated. Among these were Mau Mau General Baimungi (1964), Pio Gama Pinto (1965), Tom Mboya (1969), Ronald Ngala (1972), and JM Kariuki (1975).

JM and Pinto had been Mau Mau freedom fighters and detainees. On their respective releases, they both brought into the arena of Kenyan political activity in Independent Kenya a critical composite of thought and action - the aims of the Freedom Struggle accompanied by the continued voicing of the demands of the Mau Mau ex-detainees for their implementation.