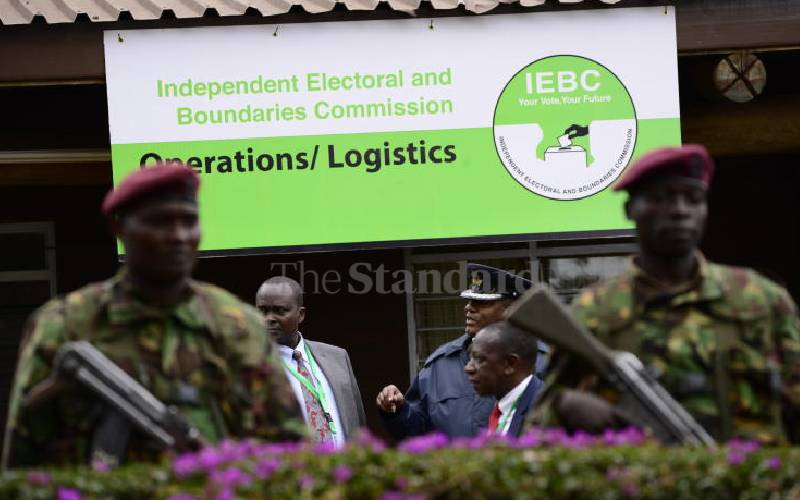

Kenyan Police stand guard at Bomas National Tallying Centre on August, 11,2017, ahead of IEBC's announcement of Kenya's president. [John Muchucha]

Emerging discussions surrounding the location of the server that houses presidential election data is a curious one. The decision to store such critical data abroad has been criticised as a vestige of colonial mentality, suggesting a lack of sovereignty over our electoral process. The argument for relocating the server to Kenyan soil is predicated on the belief that it would simplify the adjudication of election petitions.