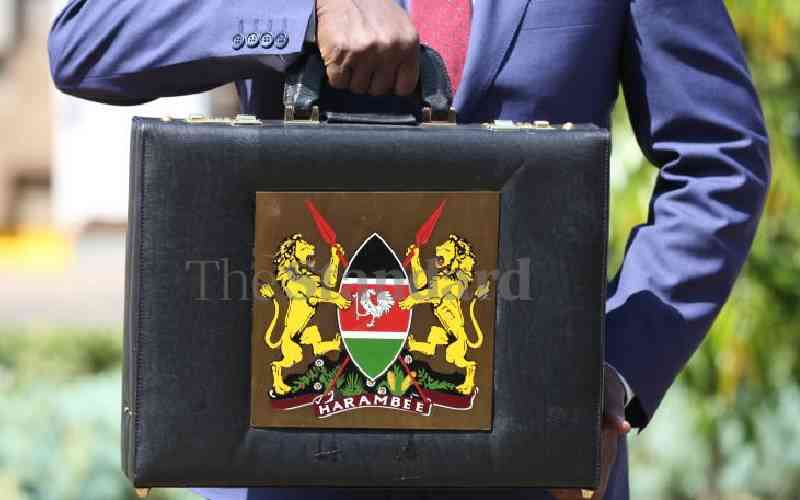

A progressive constitutional design in which the National Treasury leads in crafting the National Budget, but Parliament actually makes it, takes nothing away from the bureaucratic symbolism of Budget Day.

It isn't quite the Budget Speech common to parliamentary systems of government but Thursday's Budget Statement is still a statement of policy as set out by Parliament and articulated by Treasury. Over a decade into the 2010 Constitution, we must internalise Parliament's strengthened role as an independent law-maker in a context of party loyalties.