×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

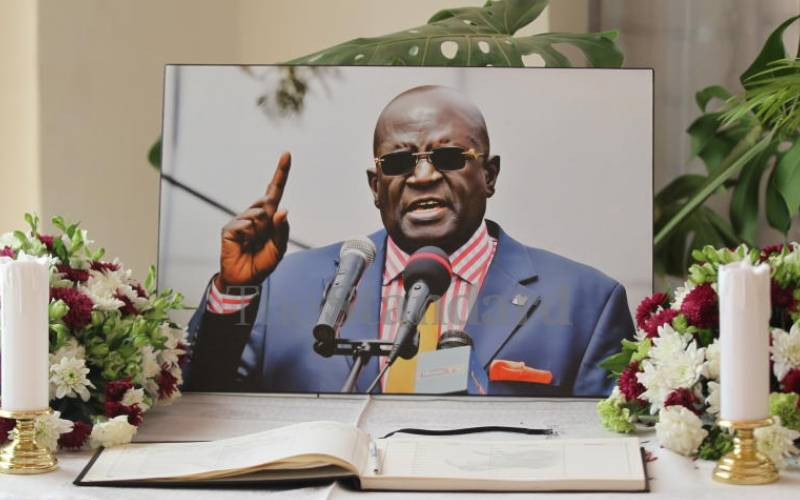

The first time I heard the word "inscrutable", I was on a phone call with Prof George Magoha. He used it in an attempt to describe himself, specifically why he never smiled or danced in public.

When I asked him what it meant, he explained it as the ability to hide emotions so well that nobody can figure out what you are thinking.