×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

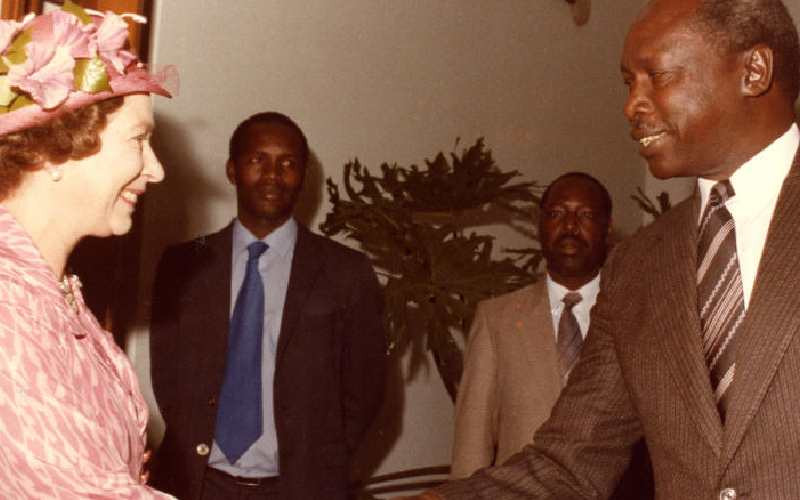

The late president Daniel Moi when he met Queen Elizabeth II. [File]

It was a big story when news reached Kenya that King George VI had died and the 25-year-old Princess visiting Kenya was now the Queen, the head of the British Monarchy.