×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

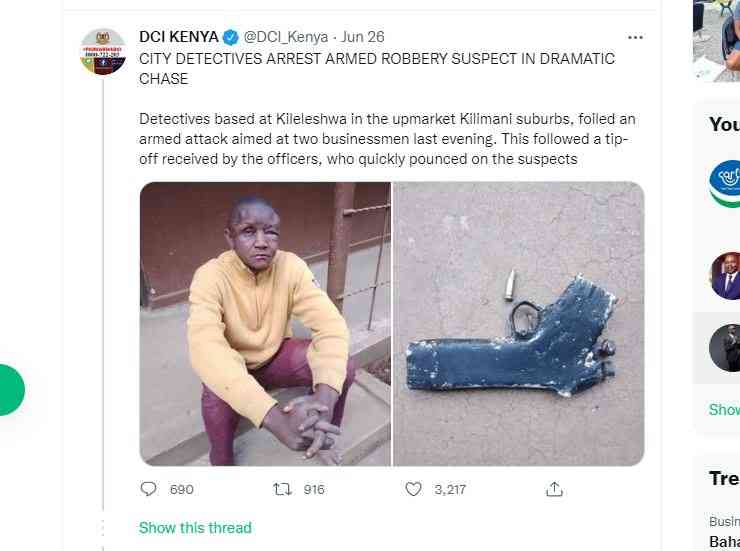

The Directorate of Criminal Intelligence (DCI) has increased its online visibility with regards to naming and shaming perceived lawbreakers on its social media handles.

Narrations and re-enactment of crimes on its Twitter and Facebook posts have created good banter among the online community. But sometimes, this has come at a steep price, especially when those named and shamed have nothing to do with the alleged crime.