×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

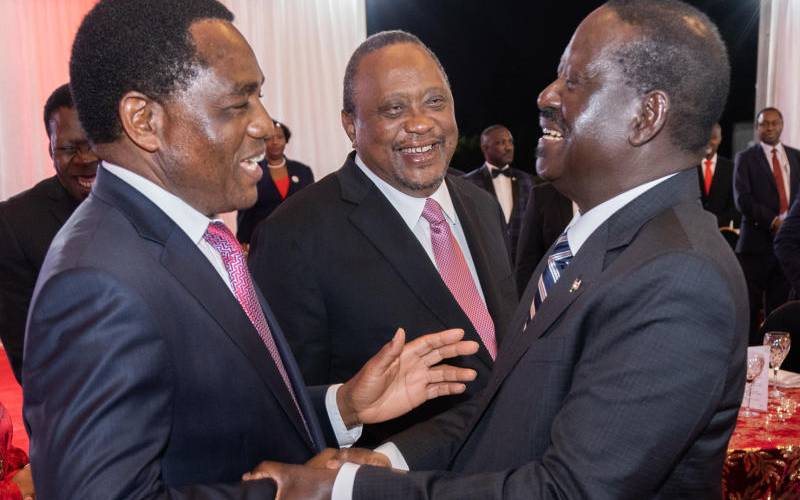

With just under two months left to the August 9 General Election, President Uhuru Kenyatta is now most clearly in the twilight days of his regime.

In a few weeks’ time, he will be referred to as “former president,” or “retired president.” His tenure will henceforth assume the various forms of the past tense, as his performance is recalled only in comparison to those before and after him.