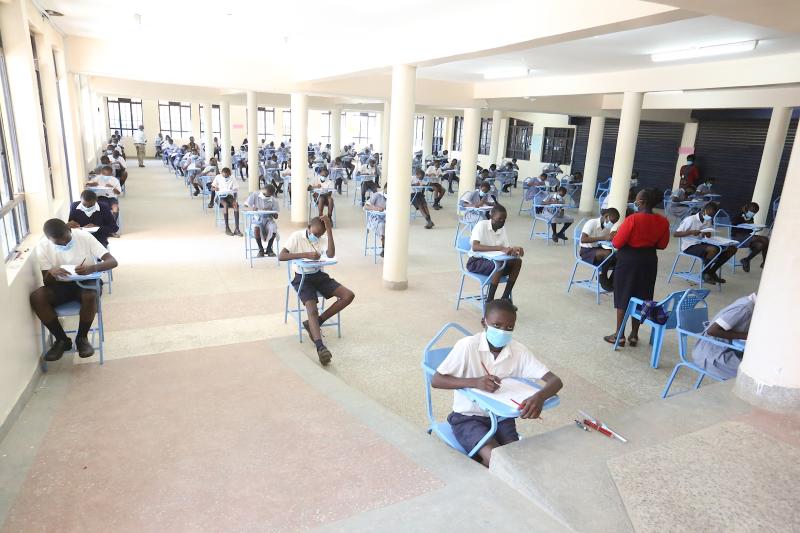

Kakamega Hill School Class Eight candidates during their KCPE Mathematics paper on March 7, 2022. [Benjamin Sakwa, Standard]

Columnist Antoney Luvinzu attributed cheating in national examinations to what he considered a traditional assessment model. In an article last week, Luvinzu argued that examination cheating can be ended when the country adopts what he called authentic assessment model. In simplified terms, the traditional assessment model measures students’ knowledge of the content. Authentic assessment, on the other hand, is said to measure students’ ability to apply knowledge of the content in simulated or real-life situations.