×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

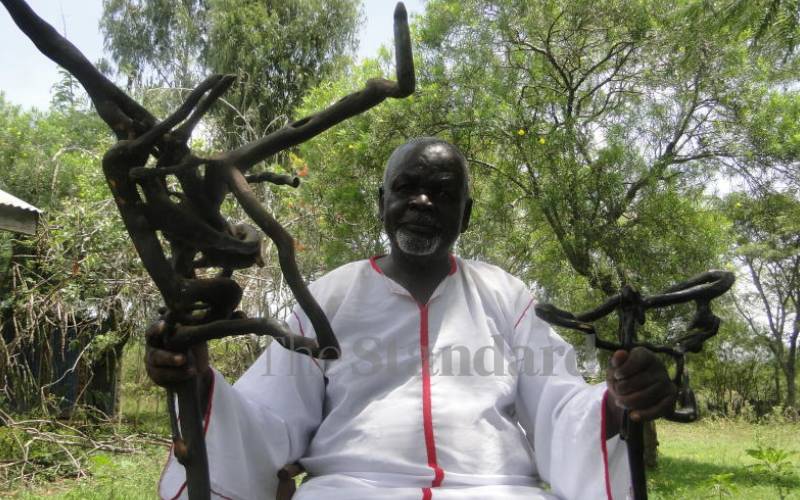

Mzee Thomas Achando, a grandson to Badia - a renowned magician in Yimbo. [Isaiah Gwengi, Standard]

When she lost her husband 15 years ago, Dorothy Aluoch was required to undergo cleansing, according to Luo traditions.