×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

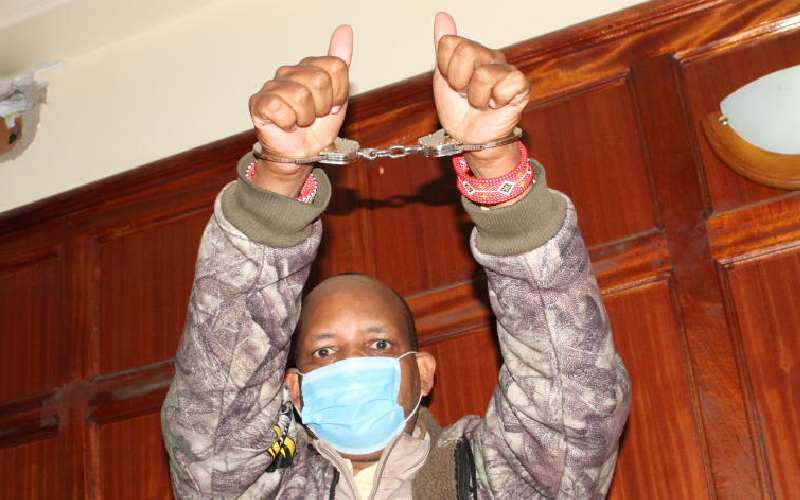

Former Laikipia North MP Mathew Lempurkel at a Milimani court on September 09, 2021, when he was arraigned at the court in connection with an offence related to hate speech. [Collins Kweyu, Standard]

A seasoned journalist made a troubling assessment of the Uhuru Kenyatta succession.