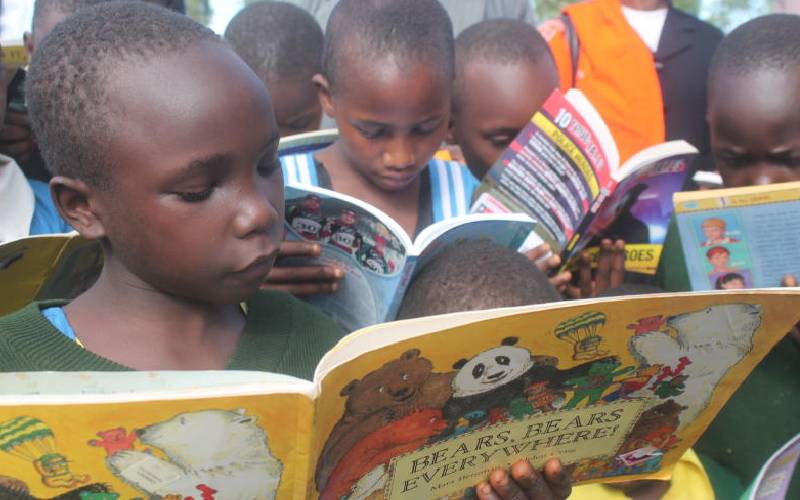

Pupils of Nyakeore Primary School read through the books which were donated to them by a group of US kids under the banner of Friends of Africa. [Stanley Ongwae, Standard]

There are plans to have Kenya Medical Training College (KMTC) offer English lessons to its students {nurses} in a bid to bridge gaps in communication skills {read English proficiency} laid bare last year when hundreds of nurses were locked out of job opportunities in the UK. This fiasco is just one of the many instances when/where prospective employers, although impressed by the technical know-how of a candidate, get frustrated by their glaring gaps in communication skills. They can’t write grammatically sound emails, can’t articulate their thoughts, can’t present a pitch etc. And language – written and oral – is the medium of communication in this context.