×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

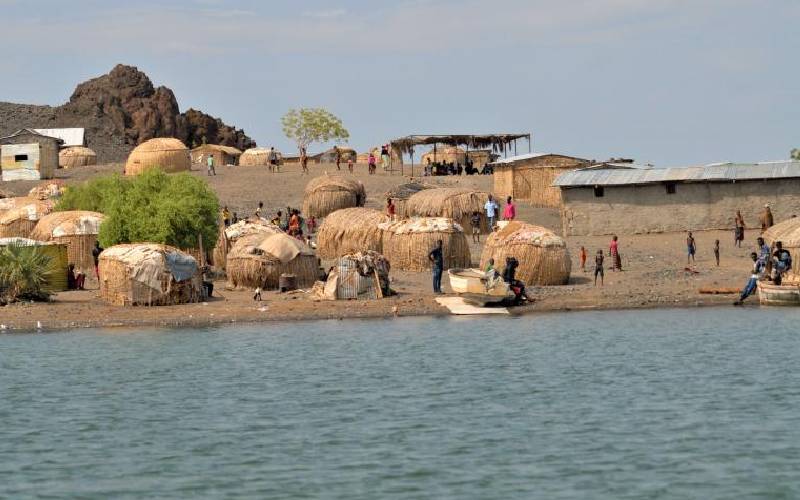

Some of the Manyattas near Lake Turkana.

I woke before the crack of dawn after a quiet night in Loiyangalani, well except for the wind that violently ruffled the palm fronds outside. It would be another hot day in the desert. It would get hotter, we were warned, as we delved further out of Loiyangalani.