×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

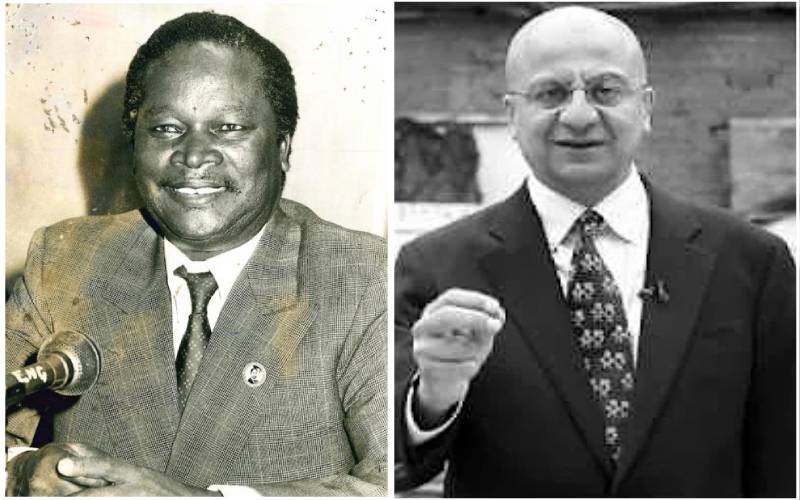

Former Cabinet Minister Nicolas Biwott and Alnoor Kassam. [Courtesy]

In his early thirties, Alnoor Kassam had already built a multi-million financial empire. What was lacking was a bank.