×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

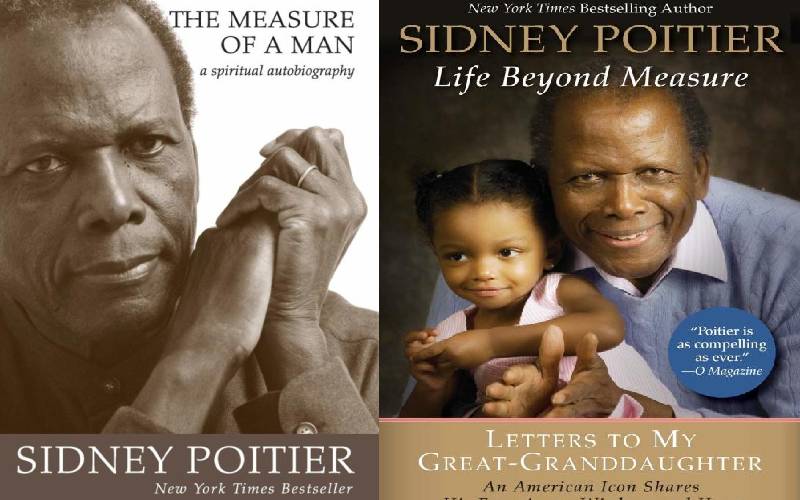

When film star Sidney Poitier died last week aged 94, there was an outpouring of praise and grief. Poitier was after all the first black man to win an Oscar. He won the Academy award for Best Actor for his role in Lillies of the Field (1963).