×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

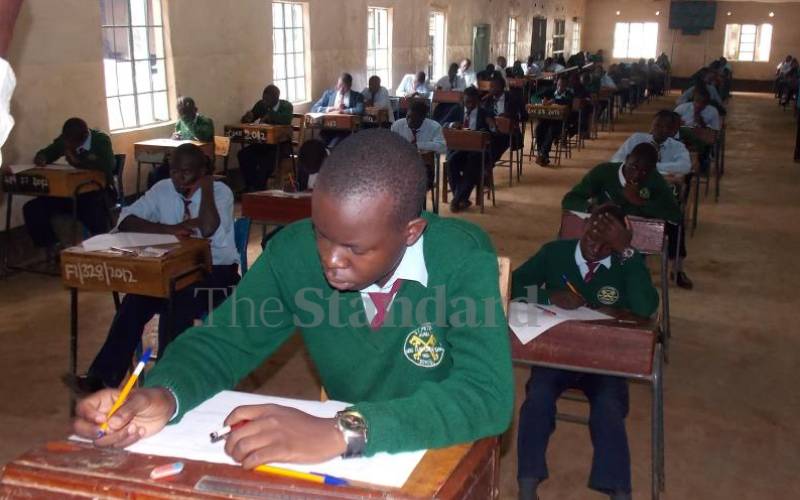

The government has downplayed the place of national examinations or assessments in the Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC). And while stakeholders have not expressed their anxieties, the worry is real.

Education officials say learners will not endure the stress of national examinations associated with 8-4-4, thanks to CBC. The students will learn without the shadow of exams. The government has replaced what they now describe as summative assessments or examinations with formative examinations.