×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

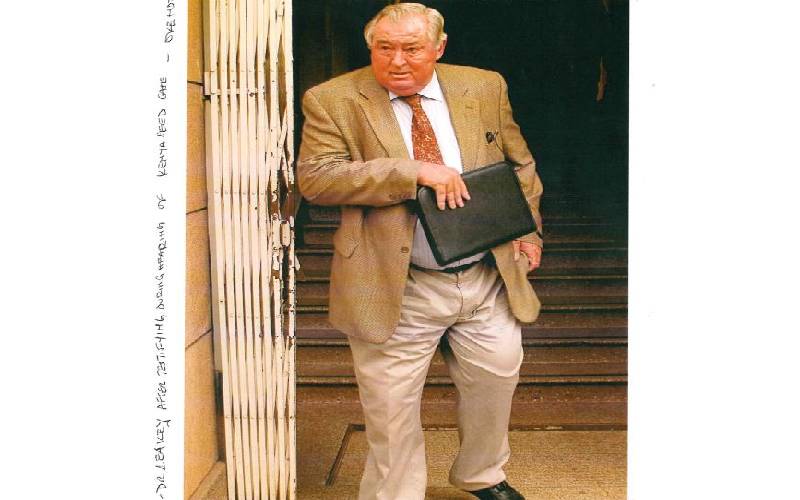

When Kenya was painfully birthing multi-party politics in 1994, one of the voices of reform that stood out was that of Dr Richard Leakey, a fierce conservationist ready to sacrifice his life for democracy.