×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands of Readers

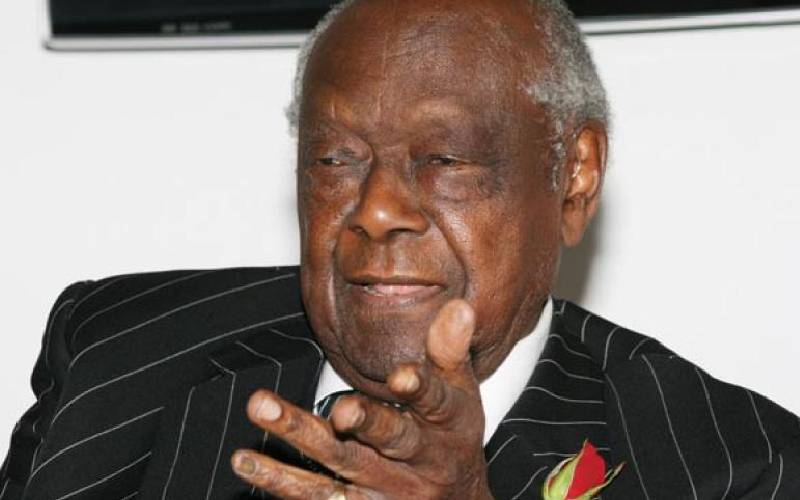

A lot has been said and written about Mr Charles Mugane Njonjo. A lot more will come. When the taps of memory of those who encountered or heard about him dry up, the final opinion of what kind of person he actually was will be left to you. But even more, the bigger judge will be his maker, whom he may have already encountered in life after this turbulent earth.